Org. Synth. 2025, 102, 45-63

DOI: 10.15227/orgsyn.102.0045

Preparation of 1,3-Dihydroxyphenazine

Submitted by Trevor Dzwiniel, Emma Markun, James A. Kaduk, Aaron Hollas, Krzystof Pupek, and Nicholas Boaz*

1Checked by Uros Vezonik, Florian Doubek and Nuno Maulide

1. Procedure (Note 1)

A. 1,3-Dihydroxyphenazine dioxide (3). A 500-mL three-necked flask equipped with an oval Teflon-coated stir bar (50 mm x 20 mm), argon inlet, and two rubber septa is charged with benzofuroxan (10.0 g, 98%, 73.4 mmol, 1.0 equiv) (Note 2), and phloroglucinol (9.26 g, 73.4 mmol, 1.0 equiv) (Note 3). Methanol (100 mL) (Note 4) is added, and the mixture stirred at room temperature under streaming argon until the solids dissolved. N,N-Diisopropylethylamine (13.8 mL, 129 mmol, 1.1 equiv) (Note 5) is added to the mixture followed by deionized water (26 mL). Upon addition of the amine and water, the solution turns a deep green color, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Reaction setup immediately upon addition of water and N,N-diisopropylamine (Photo provided by authors)

After stirring at room temperature for 18 h, the reaction is quenched by addition of 100 mL of aqueous HCl (1.2 M) (Note 6). The reaction solution is then further diluted by the addition of 200 mL of deionized water and allowed to stir for 20 min. The purple solid formed is isolated by filtration through a 150-mL medium porosity (grade 3) sintered glass funnel and washed with three 20 mL portions of deionized water (Note 7). The crude material, still in the sintered glass funnel, is resuspended in the funnel with 50 mL of ethanol (Note 8) with stirring. After the solid is resuspended and the solution resembled a slurry it is allowed to slowly filter (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Intermediate 1,3-dihydroxyphenazine dioxide being resuspended in ethanol with a metal spatula and filtered (Photo provided by authors)

The crude material is then dried for 18 h under reduced pressure using a high vacuum pump (0.2 mbar, 20 ℃) (

Note 9) to yield the crude product as a purple powder (9.62 g) (

Note 10). The dried crude powder is then added to a 250-mL Erlenmeyer flask and resuspended in 100 mL of phosphate buffer (pH 7.0, 100 mM) (

Note 11). The resulting slurry is allowed to stir vigorously overnight. The purified intermediate is then isolated by filtration through a 60-mL fine porosity sintered glass funnel (grade 4) and washed with two portions of 20 mL of deionized water to remove any residual buffer salts. The wet solid is dried for 18 h under reduced pressure using a high vacuum pump (0.2 mbar, 20 ℃) (

Note 9) to yield the intermediate as a fine purple powder (9.14 g, 51%) (

Note 12). The intermediate,

1,3-dihydroxyphenazine dioxide, is characterized by

1H NMR,

13C NMR, and IR, matching the previously published data (

Note 13).

2 This solid is recrystallized before use in the next step to yield 7.59 g

1,3-dihydroxyphenazine dioxide (42% yield overall, 83% yield for recrystallization) (

Note 14).

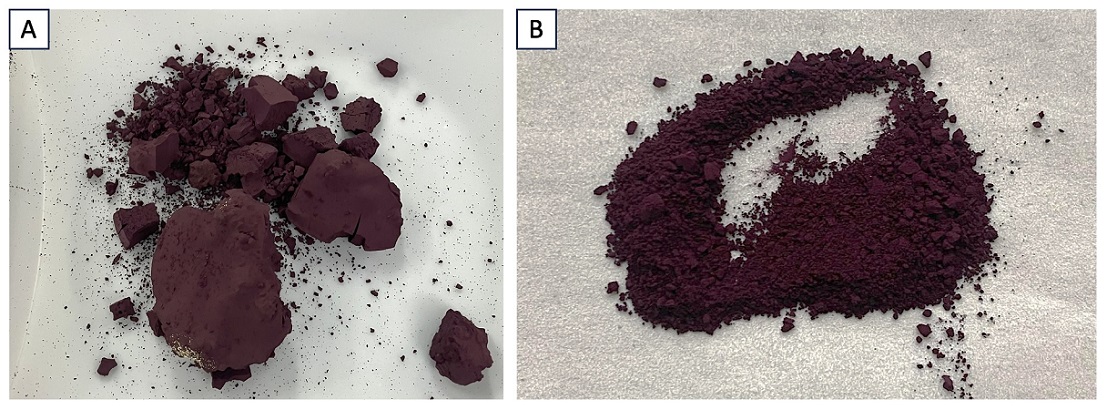

Figure 3. A) 1,3-Dihydroxyphenzine dioxide after the final drying step. (Photo provided by authors) B) Small portion of 1,3-dihydroxyphenzine dioxide after recrystallization (Photo provided by checkers)

B. 1,3-Dihydroxyphenazine (4). A 500-mL three-necked round bottom flask equipped with an oval, Teflon-coated stir bar (50 mm x 20 mm), argon inlet, and two rubber septa is charged with 1,3-dihydroxyphenazine dioxide (6.00 g, 24.6 mmol, 1 equiv) and 110 mL of deionized water. Potassium hydroxide (8.11 g, 123 mmol, 5 equiv, 85%, technical grade) is then added as a 5 mL solution to the slurried mixture of 1,3-dihydroxyphenazine dioxide. Upon addition of the base, the mixture becomes a dark green homogenous solution (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Addition of aqueous potassium hydroxide to a slurry of 1,3-dihydroxyphenazine dioxide results in the formation of a homogeneous green solution (Photo provided by authors)

The solution is allowed to stir at room temperature for 30 min under flowing argon to ensure complete dissolution.

Sodium dithionite (8.26 g, 41.8 mmol, 1.7 equiv., 88%, technical grade,

Note 16) is then added to the reaction solution over the course of 15 min. The reaction is allowed to stir for 2 h under flowing argon at which point the reaction is exposed to air and allowed to continue to stir for 18 h. The reaction is then quenched by the addition of glacial acetic acid (approximately 1 mL,

Note 17) until the solution reached a pH of 5.0, as monitored by a pH probe (due to the color of the solution). The crude product is then isolated by filtration through a 60 mL medium porosity sintered glass funnel (grade 3) and washed with two 20 mL portions of deionized water and dried for 18 h under reduced pressure using a high vacuum pump (0.2 mbar, 20 ℃) (

Note 9). The crude product (5.53 g) is redissolved in 50 mL of

N,N-dimethylformamide in a 100-mL Erlenmeyer flask equipped with an oval, Teflon-coated stir bar (50 mm x 20 mm). Decolorizing charcoal (2.5 g) (

Note 18) is added, and the mixture is allowed to stir for 24 h. The decolorizing charcoal is removed by filtering the mixture through a pad of Celite (

Note 19). The Celite pad is washed successively with 2.5 mL of

N,N-dimethylformamide and 10 mL of

acetone. Deionized water (200 mL) is added slowly (over 15 s) to the filtrate and the solution is allowed to stand for 1 h without stirring while cooling in an ice bath at 0 ℃. The solid precipitate is filtered through a 60 mL medium porosity sintered glass funnel (grade 3) and washed with two 10 mL portions of deionized water. The wet solid is dried for 18 h under reduced pressure using a high vacuum pump (0.2 mbar, 20 ℃) (

Note 9) to yield the title compound as orange-brown microneedles (2.61 g, 50% relative to starting

1,3-dihydroxyphenazine dioxide) (

Note 20). The title compound is characterized by

1H NMR,

13C NMR, IR, HR-ESI MS, Elemental Analysis, and quantitative NMR (Notes

21,

22) matching previously published reports of the compound.

2 Powder X-ray diffraction shows that freshly recrystallized

1,3-dihydroxyphenazine crystallizes as a pentahydrate. When the solid is allowed to dry, two different solid crystal forms of

1,3-dihydroxyphenazine are identified (

Note 15).

Figure 5. 1,3-Dihydroxyphenazine following final recrystallization and drying (Photo provided by authors)

2. Notes

1. Prior to performing each reaction, a thorough hazard analysis and risk assessment should be carried out with regard to each chemical substance and experimental operation on the scale planned and in the context of the laboratory where the procedures will be carried out. Guidelines for carrying out risk assessments and for analyzing the hazards associated with chemicals can be found in references such as Chapter 4 of "Prudent Practices in the Laboratory" (The National Academies Press, Washington, D.C., 2011; the full text can be accessed free of charge at

https://www.nap.edu/catalog/12654/prudent-practices-in-the-laboratory-handling-and-management-of-chemical. See also "Identifying and Evaluating Hazards in Research Laboratories" (American Chemical Society, 2015) which is available via the associated website "Hazard Assessment in Research Laboratories" at

https://www.acs.org/about/governance/committees/chemical-safety.html. In the case of this procedure, the risk assessment should include (but not necessarily be limited to) an evaluation of the potential hazards associated with

benzofuroxan,

phloroglucinol,

methanol,

N,N-dimethylformamide,

N,N-diisopropylethylamine,

ethanol,

hydrochloric acid,

potassium dihydrogen phosphate,

potassium hydroxide, and

sodium dithionite.

2.

Benzofuroxan (98%) was obtained from Thermo Scientific and used as received.

3.

Phloroglucinol was obtained from Sigma Aldrich and used as received.

4. All solvents were purchased from major suppliers and used as received. Checkers:

Methanol, HPLC grade, Fischer Scientific;

N,N-dimethylformamide (with Sure Seal), Fisher Scientific;

acetone, analytical reagent grade, Fischer Scientific. Authors:

methanol, ACS grade, Pharmco;

N,N-dimethylformamide, (with Sure Seal), Sigma Aldrich;

acetone, ACS grade, Pharmco.

5.

Diisopropylethylamine was obtained from Beantown Chemical (authors) or Sigma Aldrich (checkers) and used as received.

6. Concentrated

HCl was purchased from Pharmco (authors) or Sigma Aldrich (checkers) and used as received.

7. A fine porosity sintered glass filter (grade 4) may also be used.

8.

Ethanol, 200 proof, was purchased from Pharmco (authors) or Fisher Scientific (checkers, ACS reagent grade) and used as received.

9. The authors dried the material in a vacuum oven for 18 h (100 mm Hg, 40 ℃).

10. A second run, performed on half scale, gave 5.06 g of crude material. The authors obtained 8.49 g on full scale.

11. 100 mM phosphate buffer was made by dissolving 2.72 g of

KH2PO4 (Sigma Aldrich - authors; Merck - checkers) in 200 mL of deionized water and correcting the pH to 7.0 with

KOH (85%, Beantown Chemical - authors or Fisher Scientific - checkers).

12. A second run by the checkers, performed on half scale, gave 4.51 g (50%) yield. Two runs, performed by the authors on full scale, gave 7.78 g (43%) and 7.64 g (43%).

13. Fine purple powder.

1H NMR

pdf (600 MHz, DMSO- d

6) δ: 14.95 (s, 1H), 11.23 (s, 1H), 8.49 (dd, J = 7.9, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 8.45 (d,

J = 7.9, 1.97 Hz, 1H), 7.90 (m, 2H), 7.20 (d,

J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 6.67 (d,

J = 2.4 Hz, 1H).

13C NMR

pdf (151 MHz, DMSO-d

6) δ: 161.7, 154.8, 137.8, 135.4, 131.7, 131.6, 130.6, 122.3, 118.8, 118.6, 105.5, 90.6. IR (AT-IR) ν: 3093, 1641, 1570, 1472, 1393, 1305, 857, 804 cm

-1. mp > 250 ℃.

14. The authors reported use of the intermediate without further purification. The checkers found that, while not influencing the success of the reaction, recrystallization assures the highest reproducibility with regard to the purity of the final product.

1,3-dihydroxyphenazine dioxide (9.14 g, 36.9 mmol) was dissolved in 450 mL of

N,N-dimethylformamide and allowed to stir for 30 min to ensure complete dissolution. Water (675 mL) was then added slowly, and the solution was cooled in an ice bath without stirring. After 30 min in an ice bath the solution was filtered using a 150 mL medium porosity (grade 3) sintered glass funnel and washed with two 40 mL portions of deionized water. The purple solid was dried under a reduced pressure using a high vacuum pump (0.2 mbar, 20 ℃) for 18 h to yield 7.59 g of product. Recrystallizations by the checkers gave yields of 83% and 81% starting from the non-recrystallized material. This recrystallization produced a microcrystalline powder of sufficient quality for analysis by powder diffraction. The powder X-ray diffraction pattern obtained from this solid indicates that

1,3-dihydroxyphenazine dioxide crystallized with an equivalent of DMF and 1.5 equivalents of water (

Note 15).

15. The X-ray powder diffraction patterns of

1,3-dihydroxyphenazine dioxide (DMF)(H2O)1.5,

1,3-dihydroxyphenazine(H2O)5, and one form of

1,3-dihydroxyphenazine were measured on PANalytical Empyrean diffractometer equipped with an incident-beam focusing mirror and an X'Celerator detector. The patterns (1-50° 2θ, 0.0083556° steps, 4.0 sec/step, 1/4° divergence slit, 0.02 radian Soller slits) was measured from 0.7 mm diameter capillary specimens using Mo K

α radiation. The pattern of the second form of

1,3-dihydroxyphenazine was measured on PANalytical X'Pert Pro diffractometer equipped with an X'Celerator detector. The pattern (4-100° 2θ, 0.016711° steps, 4.0 sec/step, 1/2° divergence slit, 0.04 radian Soller slits) was measured from a flat-plate specimen using Cu K

α radiation.

16.

Sodium dithionite (88%) was purchased from Sigma Aldrich and used without further purification. Other grades of

sodium dithionite have also been used with satisfactory results. While the grade did not have an impact, the checkers found that the reaction performed significantly better with freshly obtained

sodium dithionite, as a reaction conducted with an old batch did not yield any appreciable amounts of the desired product.

17. Glacial acetic acid was purchased from Pharmco (authors) or Titolchimica (checkers) and used as received.

18. Decolorizing Charcoal (Darco

®, G-60) was purchased from J.T. Baker Chemical Company and used as received.

19. Celite

® 545 was purchased from Supelco (authors) or Sigma Aldrich (checkers) and used as received.

20. A second run, performed by the checkers on half scale, gave 1.24 g (48%). Two full-scale runs performed by the authors provided 2.71 g (52%) and 2.32 g (45%) of product.

21. Orange-brown microneedles.

1H NMR

pdf (500 MHz, DMSO-d

6) δ: 10.64 (s, 1H), 10.62 (s, 1H), 8.18 (dd,

J = 8.4, 0.8 Hz, 1H), 8.06 (dd

, J = 8.8, 0.7 Hz, 1H), 7.85 (ddd,

J = 8.6, 6.6, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.77 (ddd,

J = 8.5, 6.6, 1.4 Hz, 1H), 6.85 (d,

J = 2.37 Hz, 1H), 6.82 (d,

J=2.39 Hz, 1H).

13C NMR

pdf (126 MHz, DMSO-d

6) δ:161.0, 154.5, 145.4, 143.3, 139.2, 133.0, 130.7, 129.4, 128.3 (2C), 105.0, 98.6. IR (AT-IR) ν: 3367, 2981, 2813, 2639, 1640, 1631, 1455, 1159, 999, 860 cm

-1. HR-ESI MS

m/z calculated for C

12H

9N

2O

2 [M+H], 213.0559, found 213.0659. mp > 250 ℃.

22. Analysis by qNMR relative to an internal standard of

dibromomethane (99%, Sigma Aldrich) found the solid to be 98.5% pure by mass. The checkers reported qNMR

pdf purities by mass of 98.8% and 98.3% relative to a standard of

p-dichlorobenzene).

Working with Hazardous Chemicals

The procedures in

Organic Syntheses are intended for use only by persons with proper training in experimental organic chemistry. All hazardous materials should be handled using the standard procedures for work with chemicals described in references such as "Prudent Practices in the Laboratory" (The National Academies Press, Washington, D.C., 2011; the full text can be accessed free of charge at

http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=12654). All chemical waste should be disposed of in accordance with local regulations. For general guidelines for the management of chemical waste, see Chapter 8 of Prudent Practices.

In some articles in Organic Syntheses, chemical-specific hazards are highlighted in red "Caution Notes" within a procedure. It is important to recognize that the absence of a caution note does not imply that no significant hazards are associated with the chemicals involved in that procedure. Prior to performing a reaction, a thorough risk assessment should be carried out that includes a review of the potential hazards associated with each chemical and experimental operation on the scale that is planned for the procedure. Guidelines for carrying out a risk assessment and for analyzing the hazards associated with chemicals can be found in Chapter 4 of Prudent Practices.

The procedures described in Organic Syntheses are provided as published and are conducted at one's own risk. Organic Syntheses, Inc., its Editors, and its Board of Directors do not warrant or guarantee the safety of individuals using these procedures and hereby disclaim any liability for any injuries or damages claimed to have resulted from or related in any way to the procedures herein.

3. Discussion

The ability to effectively store energy produced by intermittent renewable sources is a critical challenge for chemists and materials scientists. Redox flow batteries (RFB), which generate current by the flow of electrons between dissolved redox active compounds in separate solutions, are envisioned as a method to store renewable energy at the electrical grid scale. The best known examples of RFBs are driven by redox active metal or main group complexes.

3,4,5,6 Within the past decade, redox active organic molecules have begun to be used in the construction of RFBs with high cell potential and cycle stability, at economical price points.

7,8,9,10,11 Of particular interest are substituted dihydroxyphenazines, a class of heterocycles, that have recently been used as an anolyte for aqueous organic RFBs.

12 Recent work indicates that different regioisomers of dihydroxyphenazine show dramatically different solubility and stability under electrochemical cycling conditions.

2 Of particular interest was 1,3-dihydroxyphenazine (Figure 6), which showed greater than 1.5 M solubility in 2M aqueous potassium hydroxide and excellent electrochemical stability. Previously reported methods of producing 1,3-dihydroxyphenazine, however, are low yielding and cumbersome.

2,13,14,15 In this work we report an improved method of producing 1,3-dihydroxyphenazine at high purity and moderate yield. This method was used by the Materials Engineering Research Facility (MERF) at Argonne National Lab to deliver more than 1.5 kg of this compound for use in the construction of aqueous organic RFBs.

Figure 6. The structure of 1,3-dihydroxyphenazine

Previous methods of producing 1,3-dihydroxyphenazine have appeared several times in the chemical literature. As shown in Scheme 1A, Yosioka and coworkers produced 1,3-dimethoxyphenazine in low yield by condensing aniline and 4-nitroresorcinol dimethylether with potassium hydroxide in refluxing toluene.

13 This intermediate, 1,3-dimethoxyphenazine, was then demethylated using hydrobromic acid in acetic acid to yield 1,3-dihydroxyphenazine. The yield of 1,3-dihydroxyphenazine produced in the demethylation step was not reported. As shown in Scheme 1B, Clemo and Daglish report the synthesis of 1,3-dihydroxyphenazine via the hydrolysis of 1,3-diaminophenazine.

14,16 The hydrolysis step proceeds in 20% yield leading to an overall 9% yield from a starting material of picaryl-

o-phenylenediamine.

Scheme 1. A. Synthesis of 1,3-DHP via an intermediate of 1,3-dimethoxyphenazine. B. Synthesis of 1,3-dihydroxyphenazine from an intermediate of 1,3-diaminophenazine

Haddadin and coworkers reported a different route to 1,3-dihydroxyphenazine using a reactive aryl nitroso intermediate.

17 As shown in Scheme 2,

o-phenylenediamine is first oxidized by peracetic acid to

o-nitrosoaniline in low yield (17%) followed by cyclization with phloroglucinol in basic methanol. From o-phenylenediamine, 1,3-dihydroxyphenazine was produced in 4% yield.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of 1,3-dihydroxyphenazine via an intermediate of o-nitrosoaniline

More recently, Wellala

et al. reported a synthesis of 1,3-dihydroxyphenazine (3) via the reduction of a 1,3-dihyroxyphenazine dioxide intermediate.

2 As shown in Scheme 3, the authors produced 1,3-dihyroxyphenazine via the condensation of benzofuroxan and phloroglucinol using potassium hydroxide in a mixture of water and THF. The intermediate was purified by recrystallization from DMSO/Acetone and DMSO/H

2O. Reduction of the

N-oxide intermediate via sodium dithionite and subsequent Soxhlet extraction with acetone yielded 1,3-dihydroxyphenazine in 16.8% yield from the starting benzofuroxan. Similar preparations of the intermediate 1,3-dihyroxyphenazine have been reported, in yields ranging from 26-32%, but to the best of our knowledge, Wellala and coworkers were the first to reduce 1,3-dihydroxyphenazine dioxide to 1,3-dihydroxyphenazine.

15,18,19Scheme 3. Synthesis of 1,3-dihydroxyphenazine via an intermediate of 1,3-dihydroxyphenazine dioxide

The procedure reported in this work for the synthesis of 1,3-dihydroxyphenzaine follows the basic scheme originally published by Wellala and coworkers.

2 As shown in Scheme 4, 1,3-dihydroxyphenazine dioxide (3) is first produced through the condensation of benzofuroxan and phloroglucinol using

N,N-diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA) in a mixed solvent of water and methanol. The intermediate was then reduced with sodium dithionite in basic water to yield 1,3-dihydroxyphenzanine in 23% overall isolated yield in two steps from benzofuroxan.

Scheme 4. New method to produce 1,3-DHP at scale

There are several advantages of the preparation in this work over previously published methods. First, the use of N,N-diisopropylethylamine in a mixed solvent of methanol and water produces 1,3-dihydroxyphenazine dioxide at higher yield than previously reported formations in basic water and THF. Moreover, the product was produced more cleanly than methods using metal hydroxide bases. The cleaner product allows a time-consuming recrystallization from DMSO/Acetone and DMSO/Water to be replaced with a pH 7 buffer wash. The solid 1,3-dihydroxyphenazine dioxide obtained is then carried forward to the next step without further purification as the small amount of impurity could be easily removed when the final 1,3-dihydroxyphenazine was purified. The reduction step of this synthesis is very similar to that originally proposed by Wellala and coworkers, but we report that a sub-stoichiometric amount of sodium dithionite (1.7 equivalents) yields a cleaner reaction with fewer side products. Lastly, the final purification by Soxhlet extraction with acetone is replaced with a recrystallization from DMF/water which is more amenable to production of the compound at scale. Finally, recrystallization of both the intermediate 1,3-dihydroxyphenazine dioxide and 1,3-dihydroxyphenazine produces microcrystalline powders suitable for powder X-ray diffraction. Powder X-ray diffraction analysis yielded a structure of 1,3-dihydroxyphenazine dioxide and 3 unique structures of 1,3-dihydroxyphenazine.

The crystal structure of 1,3-dihyroxyphenazine dioxide(DMF)(H2O)1.5 is characterized by stacks of 1,3-dihydroxyphenazine dioxide molecules along the b-axis. These stacks form layers parallel to the ab-planes, with layers of DMF/H2O and H2O molecules between them. One water molecule (on a 2-fold axis) links DMF molecules, while the other hydrogen bonds to the 1,3-dihydroxyphenazine dioxide molecules.

The crystal structure of 1,3-dihydroxyphenazine(H2O)5 is characterized by stacks of 1,3-dihydroxyphenazine molecules along the a-axis. These stacks form layers parallel to the ab-planes, with layers of H2O molecules between them. An extensive network of hydrogen bonds links both the water molecules and the 1,3-dihydroxyphenazine molecules. One form of 1,3-dihydroxyphenazine crystallizes in space group P1, with Z' = 3, while another form crystallizes in Pbca with Z' = 1 (Figure 7). Hydrogen bonding is more prominent in the orthorhombic structure, linking the molecules into chains along the c-axis.

Figure 7. Structure of 1,3-dihydroxyphenazine (parent Pbca space group) as determined via powder X-ray diffraction. The blue structure represents the experimental structure determined via Rietveld refinement while the red structure represents that indicated via DFT calculation

Appendix

Chemical Abstracts Nomenclature (Registry Number)

Benzofuroxan: 2,1,3-benzoxadiazol-1-ium-1-olate; (480-96-6)

Phloroglucinol: benzene-1,3,5-triol; (108-73-6)

N,N-Diisopropylethylamine: ethylbis(propan-2-yl)amine; (7087-68-5)

Concentrated hydrochloric acid: hydrogen chloride; (7647-01-0)

Ethanol; (64-17-5)

Potassium dihydrogen phosphate; (7778-77-0)

Potassium Hydroxide; (1310-58-3)

1,3-dihydroxyphenazine dioxide: 1,3-phenazinediol, 5, 10-dioxide (3) (25629-70-3)

Sodium Dithionite; (7775-14-6)

1,3-dihydroxyphenazine:1,3-phenazinediol; (4)(4217-35-0)

|

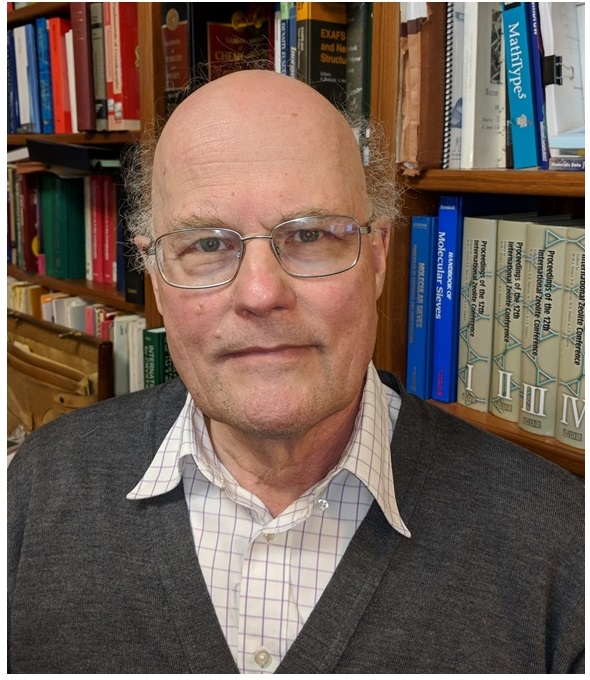

Trevor Dzwiniel completed his Ph.D. in Chemistry at the University of Alberta (Canada). After postdoctoral work at the University of Wisconsin- Madison, he spent 10 years in the pharmaceutical industry in process development groups. He joined Argonne National Laboratory in 2010, and is currently studying new materials for next gen Li-ion batteries. |

|

Emma Markun obtained her B.S. in chemistry from North Central College in Naperville, Illinois. She is currently a graduate student in the chemistry department at the University of Iowa. |

|

James A. Kaduk obtained his B. S. in chemistry from the University of Notre Dame. His doctoral work was performed under Dr. James A. Ibers at Northwestern University. After an industrial career at Amoco/BP/Ineos, he is currently a Senior Research Scientist in Physics at North Central College in Naperville IL, a Research Professor of Chemistry at Illinois Institute of Technology in Chicago IL, and President and Principal Scientist at Poly Crystallography Inc. in Naperville IL. |

|

Aaron Hollas obtained a B.S. in Chemistry from Texas A&M University and a Ph.D. in Chemistry from the University of California-Irvine. He has been at Pacific Northwest National Lab since 2016 and is currently studying new materials for redox flow batteries. |

|

Kris Pupek is a Senior Process R&D Chemist and a Group Leader for Process R&D and Scale Up, Applied Materials Division at Argonne National Laboratory. Kris graduated in 1993 with PhD in Chemistry and Chemical Technology from Institute of Organic Chemistry, Polish Academy of Sciences. He gained his hands-on experience working for nearly 20 years for various contract research and manufacturing organizations prior to joining Argonne National Laboratory in 2010. |

|

Nicholas Boaz obtained is B.S. in chemistry from Lebanon Valley College in Annville, Pennsylvania. His doctoral work was performed under Dr. John Groves at Princeton university, where he studied the mechanism of C-H oxidation by metal and non-metal oxo species. He is currently an associate professor of chemistry at North Central College in Naperville, Illinois. |

|

Florian Doubek began his studies at TU Wien in 2010, following the footsteps of his chemist parents. He completed his diploma thesis at Montan University Leoben, further solidifying his expertise in synthesis and analytical chemistry. His career spans roles as an analytical chemist and a pool table fitter. Since 2022, he has been a crucial member of the Maulide Group, working as a CTA and performing synthesis for several projects. |

|

Uroš Vezonik obtained an MSc in Chemistry from the University of Ljubljana, where he conducted research under the supervision of Prof. Janez Košmrlj. During his master's studies, he completed a research visit with Prof. David šarlah, focusing on the total synthesis of marine triterpenoids. Since 2022, he has been a graduate student in the group of Prof. Nuno Maulide, where he is developing novel synthetic methodologies based on highly reactive electrophilic species, with applications in the synthesis of natural products and pharmaceutically relevant compounds. |

Copyright © 1921-, Organic Syntheses, Inc. All Rights Reserved