Org. Synth. 2025, 102, 637-656

DOI: 10.15227/orgsyn.102.0637

Preparation of Hexafluoroisopropyl Sulfamate (HFIPS) for the Sulfamoylation of Alcohols and Amines

Submitted by Mathew L. Piotrowski, Matthew Sguazzin, Jarrod W. Johnson, and Jakob Magolan*

1Checked by Yujia Chen, Yun He, and Pauline Chiu

1. Procedure (Note 1)

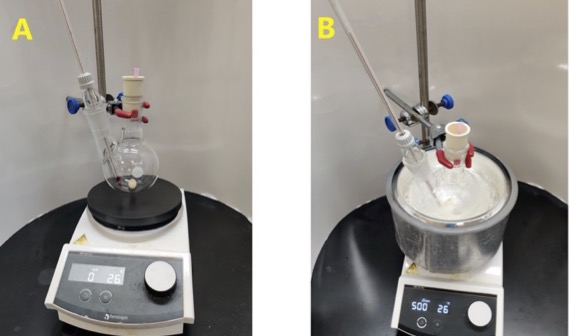

A. 1,1,1,3,3,3-Hexafluoroisopropyl sulfamate (HFIPS, 1). A two-necked (TS 24/40, 24/40) 250-mL round-bottomed flask, which was oven-dried overnight and desiccator-cooled, is equipped with a Teflon-coated magnetic stir bar (2.5 × 1.0 cm, egg-shaped), a glass thermometer adapter (TS 24/29) fitted with a low-temperature thermometer, and a rubber septum pierced with an 18G needle for venting (Figure 1A) (Note 2). Anhydrous MeCN (6.8 mL) (Note 3) is added at room temperature (22-23 ℃) via a 10-mL glass syringe (Note 4). The apparatus is then lowered into an ice-water bath and stirred until the internal temperature is below 5 ℃. Chlorosulfonyl isocyanate (CSI, 6.8 mL, 1.3 equiv) (Notes 5) is added via a 10-mL glass syringe to the MeCN at 0 ℃ over a period of 2 min, and stirring (500 rpm) is maintained until the solution again reaches below 5 ℃. Formic acid (2.8 mL, 1.25 equiv) (Note 6) is added dropwise with caution via a 6-mL plastic syringe over a period of 20 min, such that the temperature was maintained below 12 ℃ (Figure 1B). Caution is exercised during the addition due to gas evolution and temperature increase (Note 7). Following the addition, the solution is stirred for an additional 15 min before the ice-water bath is removed. The reaction is then stirred for 2.5 h at room temperature (22-23 ℃) (Note 8). The reaction vessel is lowered into an ice-water bath, and the contents are stirred with cooling until the internal temperature reaches below 5 ℃.

Figure 1. Synthesis of HFIPS. A. Assembled reaction apparatus; B. Reaction set-up with CSI, formic acid and MeCN in an ice-water bath. (Photos provided by checkers)

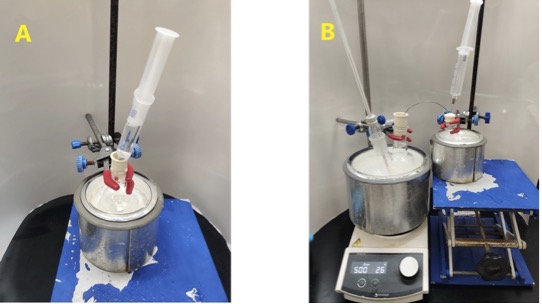

A separate 25-mL round-bottomed flask is charged with hexafluoroisopropanol (HFIP, 9.95 g, 59.2 mmol, 1.0 equiv) (Notes 9-10) and dimethylacetamide (DMA, 6.8 mL) (Note 11). This flask is placed in an ice-water bath and swirled to mix the contents (Figure 2A) (Notes 12-13). The HFIP-DMA solution is then transferred, with stirring, to the reaction flask dropwise via a cannula, using an air-filled 24-mL syringe to apply controlled pressure over a period of 20 min, such that the internal reaction temperature is maintained below 10 ℃ (Figure 2B). The 25-mL round-bottomed flask is rinsed with DMA (2 mL) and the rinse is added to the reaction flask via cannula. After 10 min, the ice-water bath is removed and stirring is continued at room temperature overnight (22-23 ℃) (18 h).

Figure 2. A. HFIP and DMA are added to a 25-mL round-bottomed flask in an ice-water bath; B. The HFIP-DMA solution is transferred to the reaction flask via a cannula. An air-filled syringe is used to apply pressure from the 25-mL flask while an outlet needle is still lodged in the septum of the reaction flask (Photos provided by checkers)

The apparatus is placed in an ice-water bath and cooled until the internal temperature is below 5 ℃ prior to quenching the reaction with water (Note 14). A total of 30 mL of water is added dropwise slowly in portions (2 x 2 mL over 2 min for each addition, then 26 mL added over 2 min) such that the internal temperature is maintained below 25 ℃.

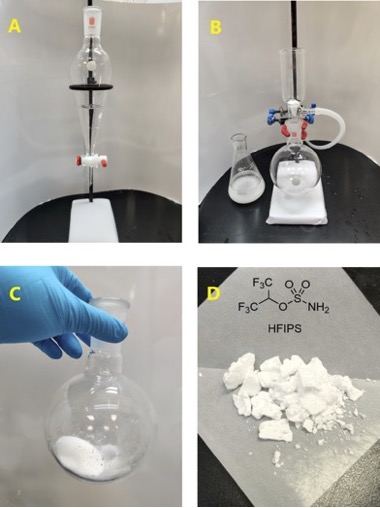

The ice-water bath is removed. The reaction mixture is transferred to a 250-mL separatory funnel and extracted with Et2O (3 × 50 mL) (Figure 3A) (Note 15). The organic extracts are combined and washed with H2O (3 × 50 mL), 10% LiCl (25 mL) (Note 16), saturated aqueous NaCl (50 mL) (Notes 17-18), then dried over anhydrous Na2SO4 (20 g) (Note 19) (Figure 3B). The Na2SO4 is removed by filtration through a cotton plug under house vacuum (~75 mm Hg). The clear, colorless filtrate is concentrated by rotary evaporation (45 ℃, 650 mbar to 200 mbar). The resulting clear, colorless oil is placed under high vacuum (15 mbar) and solidifies after about 1 h (Figure 3C). Large masses of the white amorphous solid are broken up with a spatula, then placed under high vacuum again (15 mbar, 2 h). HFIPS (10.53 g, 42.62 mmol, 72%) is obtained as a free-flowing powder without further purification (Figure 3D) (Notes 20,21,22,23,24,25).

Figure 3. A. Biphasic mixture after transferring to a separatory funnel; B. Drying the organic phase over anhydrous Na2SO4 and filter apparatus; C. and D. HFIPS (1) following workup and evacuating under high vacuum. (Photos A-C provided by the checkers; Photo D provided by the authors)

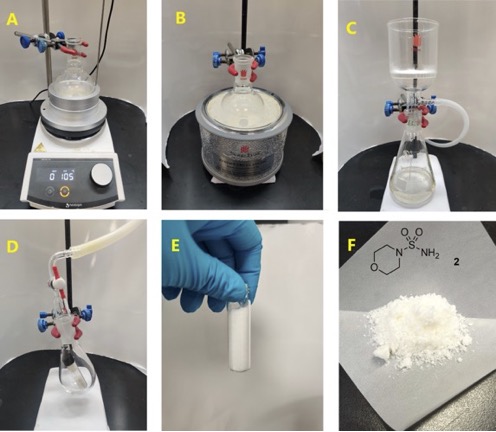

B. N-Sulfamyl morpholine (2). A two-necked (TS 24/29, 14/23) 100-mL round-bottomed flask is equipped with a Teflon-coated magnetic stir bar (2.0 × 0.9 cm, egg-shaped), a glass thermometer adapter (TS 14/23) fitted with a low-temperature thermometer, and a rubber septum pierced with an 18G venting needle (Figure 4A). The flask is charged with pyridine (23.0 mL) (Note 26), followed by morpholine (2.02 g, 23.1 mmol, 1.0 equiv) (Note 27) via syringe. The solution is stirred (500 rpm) at room temperature (22-23 ℃), then solid HFIPS (8.58 g, 34.7 mmol, 1.5 equiv) is added in one portion (Note 28) (Figure 4B). The resulting pale-yellow reaction mixture is stirred at room temperature overnight (18 h) (Figure 4B).

Figure 4. Sulfamoylation of morpholine. A. Assembled reaction apparatus; B. Reaction after 18 h at room temperature. (Photos provided by the checkers)

The reaction mixture is transferred to a single-necked (TS 24/40) 250-mL round-bottomed flask, using H2O (10 mL) to rinse and transfer. The mixture was then diluted with additional H2O (60 mL) for the azeotropic removal of pyridine. The diluted reaction mixture is concentrated on a rotary evaporator (50 ℃, 50 mbar) operating inside a fume hood, to provide a white solid. Residual pyridine is further removed by adding a second portion of H2O (20 mL) and additional rotary evaporation. Residual H2O is removed azeotropically by two rounds of rotary evaporation with PhMe (2 × 40 mL, Note 29). The flask is then placed under high vacuum (15 mbar) for 3 h to yield the product as a sticky white solid. Absolute EtOH (35 mL) is added to the round-bottomed flask containing crude sulfamide (Note 30), and the resulting slurry is heated to boiling (EtOH, b.p. = 78 ℃) over a hot plate fitted with an aluminum block (Figure 5A). Once the solids are fully dissolved, the round-bottomed flask is removed from heat and allowed to cool to room temperature (22-23 ℃) over 30 min, during which time sulfamide 2 begins to precipitate as white needles. To induce further crystallization, the round-bottomed flask is placed in an ice-water bath for 30 min (Figure 5B). The precipitate is isolated by vacuum filtration (~75 mm Hg) using a Büchner funnel lined with a round piece of filter paper (Figure 5C) (Note 31). The solids are washed by disconnecting the vacuum, then slowly adding pre-cooled absolute EtOH (50 mL) to the solids on the Buchner funnel, allowing the solvent to mix with the solids, then reconnect the vacuum to drain the liquid. The solids are left to dry on suction for 10 min. The solids are transferred to an 8-mL vial that is loosely capped, and the capped vial is placed inside a 100-mL pear-shaped flask (TS 24/40), connected to high vacuum (1 mbar) to dry overnight (16 h) (Figure 5D) to provide sulfamide 2 (2.90 g, 17.5 mmol, 75%) as a white crystalline solid (Figures 5E, 5F) (Note 32-33).

Figure 5. A. Heating crude 2 in EtOH over hot plate fitted with an aluminum block; B. Sulfamide 2 crystallizes in ice-water bath; C. Isolation of compound 2; D. Vial containing compound 2 in pear-shape flask placed under high vacuum; E. and F. N-Sulfamyl morpholine (2) after evacuating under high vacuum. (Photos A-E provided by the checkers, Photo F provided by the authors)

2. Notes

1. Prior to performing each reaction, a thorough hazard analysis and risk assessment should be carried out with regard to each chemical substance and experimental operation on the scale planned and in the context of the laboratory where the procedures will be carried out. Guidelines for carrying out risk assessments and for analyzing the hazards associated with chemicals can be found in references such as Chapter 4 of "Prudent Practices in the Laboratory" (The National Academies Press, Washington, D.C., 2011; the full text can be accessed free of charge at

https://www.nap.edu/catalog/12654/prudent-practices-in-the-laboratory-handling-and-management-of-chemical. See also "Identifying and Evaluating Hazards in Research Laboratories" (American Chemical Society, 2015) which is available via the associated website "Hazard Assessment in Research Laboratories" at

https://www.acs.org/about/governance/committees/chemical-safety.html. In the case of this procedure, the risk assessment should include (but not necessarily be limited to) an evaluation of the potential hazards associated with

chlorosulfonyl isocyanate (

CSI),

acetonitrile (

MeCN),

formic acid (

HCO2H),

hexafluoroisopropanol (

HFIP),

dimethylacetamide (

DMA),

diethyl ether (

Et2O),

morpholine,

pyridine,

toluene (

PhMe), and

ethanol (

EtOH).

2. The authors used the following: stir bar (Fisher, 14-513-62), thermometer B24 inlet adapter (ChemGlass, CG-1042-01), 1.5-inch 20-gauge PrecisionGlide needle (BD 305176). The checkers used a Quickfit cone/screwthread adapter (Aldrich Z302325) in the apparatus, and a 1.5-inch 18-gauge Terumo Agani needle (AN*1838S1) for venting.

3. The authors used anhydrous

acetonitrile (

MeCN) which was purchased from Fisher and dried by pressure filtration under argon through activated alumina. The checkers purchased

acetonitrile (99.9%, Superdry, with molecular sieves) from J&K Scientific Ltd., which was used as received.

4. This reaction was run open to air. When inert atmosphere and strictly anhydrous conditions were used in separate preparations, the isolated yields of

HFIPS were similar. The use of high-quality

CSI with anhydrous

MeCN and

DMA is sufficient to achieve high yields.

5.

Chlorosulfonyl isocyanate (

CSI) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (98%) and used as received.

CSI from Oakwood (99%) is also acceptable. We strongly recommend using a recently purchased bottle of

CSI for this reaction. Yields of HFIPS were reduced when older samples of

CSI were used.

CSI should be stored at 2-8 ℃. The checkers purchased

CSI from Energy Chemical (98%), which was used as received.

6.

Formic acid (≥96%) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (695076) and used as received. The checkers purchased

formic acid (98-100%) from Fisher Scientific, which was used as received.

7. Gas evolution is observed for the first hour following the addition. In preparations of

HFIPS using

CSI of lower quality, the addition of

formic acid increased reaction temperature to a greater extent and gas evolution was more violent. When high-quality

CSI was used and

formic acid was added slowly with rapid stirring, gas evolution and temperature increases are diminished.

8. The authors observed that while stirring at room temperature (22-23 ℃) following the addition of

formic acid, the reaction mixture becomes cloudy. The checkers did not observe any cloudiness develop.

9.

Hexafluoroisopropanol (

HFIP) was purchased from Oakwood Chemicals (99.5%) and used as received. The checkers purchased

HFIP (≥99.5%) from Shanghai Aladdin Bio-Chem Technology Co., Ltd., which was used as received.

10. For improved accuracy, the limiting liquid reagents (i.e.,

hexafluoroisopropanol (

HFIP),

morpholine) were measured by mass rather than volume. An empty plastic syringe equipped with a needle was used to withdraw

HFIP (~6.4 mL), then the needle end was protected by inserting into a rubber septum to prevent contamination and leakage (Figure 6A). This filled syringe was weighed on the balance, and the mass is recorded (Figure 6B). The septum was disengaged and the round-bottomed flask was charged with the contents of the syringe. The emptied syringe was recapped using the same septum and the entire syringe ensemble was weighed again on the balance. The mass difference is the quantity of HFIP used in the experiment.

Figure 6. Weighing liquid reagents in a syringe. A. Needle end of the filled syringe is protected by inserting into a rubber septum; B. The filled syringe is weighed on the balance. (Photos provided by checkers)

11. Anhydrous

N,N-dimethylacetamide (

DMA) was purchased from Oakwood Chemicals (99%) and dried over activated 4-Å molecular sieves prior to use. The Checkers purchased

DMA (99.5%, Superdry, with molecular sieves) from J&K Scientific Ltd., which was used as received.

12. The combination of

DMA with

HFIP is exothermic and results in increased temperature and cloudy vapor formation upon addition. A cooling bath was considered beneficial to prevent any loss of

HFIP due to evaporation.

13. The addition of a pre-mixed solution of

DMA and

HFIP is preferable over the sequential addition of

DMA and

HFIP to the reaction mixture. If

DMA is added separately prior to

HFIP, a considerable increase in reaction temperature is observed, the reaction mixture becomes cloudy and viscous overnight, and a lower yield of

HFIPS is obtained (27%).

14. A considerable increase in temperature and bubbling is observed upon quenching with the initial addition of water. Slow addition with vigorous stirring is necessary to maintain the temperature below 25 ℃ and control gas release.

15.

Ethyl acetate (

EtOAc) can be used as an alternative to

diethyl ether (

Et2O) for the extraction, but

DMA is more efficiently removed with aqueous washes when

Et2O is used. The Checkers purchased

diethyl ether (99.5%, AR grade) from RCI Labscan Ltd., which was used without further purification.

16. Washes with 10% (w/v) aqueous LiCl (i.e., 10 g LiCl per 100 mL) aid in the removal of residual

DMA from the organic extracts. The checkers purchased LiCl (99%) from J&K Scientific Ltd purchased

17. The checkers purchased NaCl (AR grade) from Dieckmann (Hong Kong) Chemical Industry Co. Ltd., which was used as received.

18. Many sulfamates and sulfamides are resistant to many standard TLC stains and can be difficult to detect at low concentrations, but

HFIPS can be visualized by staining with

KMnO4 or by negative staining with iodine (Figure 7A). Residual

DMA impurities remaining after aqueous washes elute at

Rf = 0.07 (30%

EtOAc/Hex) and stain with iodine.

Figure 7. Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) of A. HFIPS (1) and B. sulfamide (2). UV active spots are marked with dotted circles. C marks the lane of co-spots. (Photos provided by checkers)

19. The Checkers purchase anhydrous

Na2SO4 (AR grade) from Dieckmann (Hong Kong) Chemical Industry Co. Ltd., which was used as received.

20.

HFIPS (

1):

Rf = 0.55 (30%

EtOAc/hexanes), visualized with iodine then

KMnO4 (Figure 7A). M.p. 56.3-57.0 ℃ (lit. 52-55 ℃)

13;

1H NMR

pdf (500 MHz, DMSO-

d6) δ 8.50 (s, 2H), 6.22 (hept,

J = 6.1 Hz, 1H);

13C NMR

pdf (151 MHz, DMSO-

d6) δ 120.5 (qd,

J = 283, 4.1 Hz, 2C), 70.6 (hept,

J = 33.5 Hz);

19F NMR

pdf (376 MHz, DMSO-

d6) δ -72.41; IR (neat): 3396, 3293, 2977, 1534, 1374, 1353, 1292, 1248, 1188, 1106, 1064, 883, 815, 686 cm

-1; HRMS-ESI (

m/

z) [M-H]

-: 245.9665, calc'd for C

3H

2F

6NO

3S

-, Found 245.9662. The purity of

1 was determined to be 99.5% by qNMR

pdf using

1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene (99.99% ± 0.20%, purchased from Sigma-Aldrich) as internal standard. The authors obtained

1 in 70% yield and >99 wt% purity, using

1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene (Aldrich, 99.97%) as the internal standard.

21. A second full scale reaction performed by the Checkers provided 9.60 g (65% yield) of compound

1 of 99.7% purity as determined by qNMR.

22. For qNMR experiments, purity was calculated using the following equation.

where P refers to purity (wt%), std refers to internal standard, mg refers to the amount in milligrams of compound weighed for analysis, MW refers to molecular weight, I refers to proton integral area, and nH refers to the number of hydrogens associated with the NMR peak.

23. Traces of

DMA in the sample of

HFIPS are observed in the

1H NMR spectrum: d 2.94 (s, 3H), 2.78 (s, 3H), 1.96 (s, 3H). These signals integrate to 0.02 and represent 0.6% of the total weight (

Note 20).

24.

HFIPS can be further purified by flash chromatography if desired (15→100%

EtOAc/Hex)

16 (See

Note 18).

25. When dry and free of

DMA (<1% by NMR), samples of

HFIPS have been stable at room temperature (22-23 ℃) for more than 1 year. However, samples of

HFIPS are typically stored in a freezer at -20 ℃ in sealed moisture-proof containers.

26. Anhydrous

pyridine was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (99.8%) and used as received. The checkers purchased anhydrous

pyridine (99.5%) from J&K Scientific Ltd., which was used as received.

27.

Morpholine was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (>99%) and used as received. The Checkers purchased

morpholine (≥99%) from Shanghai Aladdin Bio-Chem Technology Co., Ltd., and used as received.

28. The internal reaction temperature briefly rises to 28-30℃ with the addition of

HFIPS to the

pyridine solution. After 30 min of stirring, the mixture returns to room temperature (22-23 ℃).

29. The Checkers purchased

toluene (99.5%, GR) from Duksan Pure Chemicals Ltd., which was used as received.

30. The Checkers purchased absolute

ethanol (99.5%, ACS) from Scharlau General Chemicals, which was used as received.

31. The authors used Whatman #1 filter paper. The checkers used a 150-mL Synthware Büchner funnel with perforated plate (Part no. F966024), and Synthware filter paper, 65 mm (Q101565).

32.

N-Sulfamyl morpholine (

2):

Rf = 0.40 (10% MeOH/CH

2Cl

2), visualized with

KMnO4 (Figure 7B). MP 159.6-160.9 ℃.

1H NMR

pdf (500 MHz, DMSO-

d6) δ 6.82 (s, 2H), 3.68-3.62 (m, 4H), 2.94-2.88 (m, 4H).

13C NMR

pdf (126 MHz, DMSO-

d6) δ 65.2 (2C), 45.9 (2C). IR (neat): 3297, 3175, 3087, 2868, 1459, 1349, 1263, 1149, 1107, 1069, 935, 724 cm

-1. HRMS-ESI (

m/

z) [M + H]

+: 167.0485 calc'd for C

4H

11N

2O

3S

+; Found 167.0485. The purity of

2 was determined to be 99.7% by qNMR

pdf using 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene (99.99% ± 0.20%, purchased from Sigma-Aldrich) as internal standard. The authors obtained

2 in 78% yield and >97 wt% purity, using 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene (Aldrich, 99.97%) as the internal standard.

33. A second full scale reaction performed by the Checkers provided 2.84 g (73% yield) of compound

2 of 98.9% purity as determined by qNMR.

Working with Hazardous Chemicals

The procedures in

Organic Syntheses are intended for use only by persons with proper training in experimental organic chemistry. All hazardous materials should be handled using the standard procedures for work with chemicals described in references such as "Prudent Practices in the Laboratory" (The National Academies Press, Washington, D.C., 2011; the full text can be accessed free of charge at

http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=12654). All chemical waste should be disposed of in accordance with local regulations. For general guidelines for the management of chemical waste, see Chapter 8 of Prudent Practices.

In some articles in Organic Syntheses, chemical-specific hazards are highlighted in red "Caution Notes" within a procedure. It is important to recognize that the absence of a caution note does not imply that no significant hazards are associated with the chemicals involved in that procedure. Prior to performing a reaction, a thorough risk assessment should be carried out that includes a review of the potential hazards associated with each chemical and experimental operation on the scale that is planned for the procedure. Guidelines for carrying out a risk assessment and for analyzing the hazards associated with chemicals can be found in Chapter 4 of Prudent Practices.

The procedures described in Organic Syntheses are provided as published and are conducted at one's own risk. Organic Syntheses, Inc., its Editors, and its Board of Directors do not warrant or guarantee the safety of individuals using these procedures and hereby disclaim any liability for any injuries or damage claimed to have resulted from or related in any way to the procedures herein.

3. Discussion

Sulfamates and sulfamides can be used as precursors for nitrenes, which can undergo metal-catalyzed C-H insertions or aziridinations.

2,3,4,5,6 Primary sulfamates and sulfamides are often synthesized using a two-step sequence involving the conversion of CSI to sulfamoyl chloride (

3),

7 followed by the addition of an alcohol or amine nucleophile (Figure 8A). Sulfamoyl chloride (

3) is reactive, sensitive to hydrolysis, decomposes in solution, and a large excess (1.5-4 equiv.) is often required for sulfamoylation.

8 Alternative Burgess-like reagents

4-

6 have been developed for improved stability, but require a subsequent step for Boc removal (Figure 8B).

9,10,11 Aryl sulfamates

7a and

7b are bench-stable when dry, but also show high reactivity with alcohols with catalytic

N-methylimidazole (NMI) in THF.

12Figure 8. Sulfamyl chloride for sulfamoylation A. and B. Improved reagents, and C. Sulfamates and sulfamides synthesized with HFIPS (1)

HFIPS (

1), which was reported as a reagent for sulfamoylation in 2021, is a bench-stable solid (

Note 25) that also reacts with nucleophiles under mild conditions (e.g., pyridine, CH

2Cl

2, rt), but HFIPS has the added benefit of releasing HFIP (hexafluoroisopropanol) - a volatile leaving group - as the sole byproduct (Figure 8C).

13,14 Sulfamate and sulfamide products (e.g.,

8-

17) can often be isolated in high purity by the simple removal of solvents via rotary evaporation, or through a standard aqueous workup. Overall, HFIPS offers substantially improved operational simplicity for sulfamoylation compared to the two-step method using ClSO

2NH

2 (

3).

Several groups have previously synthesized HFIPS using the two-step procedure that generates ClSO

2NH

2 (

3) from CSI (2-4 equiv.),

15,16,17,18 but we sought to improve the reproducibility of the reaction and reduce the excess of CSI used. We found that the addition of formic acid to a solution of CSI in MeCN,

16 rather than neat CSI, was beneficial for controlling the rise in temperature and rate of gas evolution. In the subsequent step, we found it most reproducible to add the HFIP as a solution in DMA, rather than separate additions of HFIP and DMA. The addition of DMA to the reaction mixture is exothermic and a rapid reaction temperature increase can be avoided if HFIP and DMA are combined and cooled to room temperature prior their addition to the reaction mixture. As reported by Okada et al., DMA and

N-methylpyrrolidone (NMP) are superior solvents to DMF, CH

2Cl

2, and DME, and the use of Et

3N as a base in the reaction is detrimental, presumably due to base-induced decomposition of sulfamoyl chloride (

3).

8 Using of CSI as a solution in MeCN and pre-mixing HFIP with DMA, helps to improve temperature control, reduces the CSI required (1.3 equiv), and improves atom-economy.

HFIPS reacts with both alcohols and amines under mild conditions. Pyridine is superior to Et3N, 4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP), and 1,8-diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene (DBU), potentially due to base-induced decomposition of HFIPS or polymerization. Pyridine can be used in small excess (2 equiv, as a co-solvent (3:7) with CH2Cl2, THF, PhMe, MeCN, or DMF, but reaction rates are highest when it is used as the sole solvent.

Upon reaction completion, the solvents can be removed by rotary evaporation with the bath as high as 50 ℃. Sulfamides and

O-alkyl sulfamates are stable under these conditions, but

O-aryl sulfamates are unstable. For

O-aryl sulfamates, a standard aqueous workup is used to remove the pyridine prior to concentration under reduced pressure. Most sulfamates and sulfamides are also stable to chromatographic purification, although many can be difficult to visualize with common stains used for TLC.

13 In this report, we present a procedure for the synthesis of

N-sulfamoyl morpholine (

2) but provide an alternate method for purification. We chose to purify this sulfamide by recrystallization because its high solubility in water led to inefficient extractions into EtOAc and CH

2Cl

2. Instead of an aqueous workup, we found that pyridine removal by rotary evaporation was facilitated by azeotropic distillation with water. Residual water was then evaporated through azeotropic removal with PhMe. Recrystallization from ethanol provided the sulfamide

2 as white crystals.

The mild conditions for sulfamoylations with HFIPS have enabled reactions with sensitive substrates such as

18 and

19 (Figure 9A).

19,20 Epoxides

20 and aziridines

21 then underwent regioselective ring-opening with pendant sulfamates. Sulfamates prepared with HFIPS have also been used as building blocks in total synthesis (Figure 9B). A stereoselective aza-Michael cyclization with homoallylic sulfamate

23 and a stereospecific ring-opening with KOAc were key steps in controlling the stereochemistry in intermediate

24, which was taken to (-)-negamycin

tert-butyl ester. Similarly, sulfamate

25 was subjected to a stereoselective aza-Wacker cyclization and subsequent S

N2 ring-opening with NaN

3 to control the stereochemistry of

25, a precursor of (+)-kasugamycin.

21Figure 9. Sulfamoylations with HFIPS and synthetic applications of highly functionalized sulfamates

Appendix

Chemical Abstracts Nomenclature (Registry Number)

Chlorosulfonyl isocyanate (CSI); (1189-71-5)

Formic acid; (64-18-6)

1,1,1,3,3,3-Hexafluoro-2-propanol (HFIP); (920-66-1)

N,N-Dimethylacetamide (DMA); (127-19-5)

1,1,1,3,3,3-Hexafluoro-2-propyl sulfamate (HFIPS); (637772-38-4)

Pyridine (110-86-1)

Morpholine (110-91-8)

N-Sulfamyl morpholine (25999-04-6)

|

Mathew Piotrowski received a B.Sc. in chemistry and completed a Ph.D. in organic chemistry at Western University, Canada, under the guidance of Prof. Michael Kerr. In 2019 he joined the Magolan lab at McMaster University. His research interests include natural products, synthetic methodology, and medicinal chemistry, and he leads collaborative medicinal chemistry projects in the lab. |

|

Matthew Sguazzin was born in Toronto, Canada in 1996. He received his BSc. in 2019 from the University of Waterloo. In 2024, he received his Ph.D. from McMaster University under the supervision of Professor Jakob Magolan. His research interests are organic methodologies and medicinal chemistry. |

|

Jarrod Johnson received a B.Sc. in biochemistry and completed a Ph.D. in organic chemistry from the University of Waterloo. His postdoctoral research at the University of Notre Dame with Prof. Shahriar Mobashery focused on antibiotics. In 2014 he returned to Canada to work with Prof. Gerry Wright in natural product discovery at McMaster University. In 2018 he joined the Magolan lab at McMaster where he is involved with organic synthesis and medicinal chemistry projects. |

|

Jakob Magolan is a Professor and Boris Family Endowed Chair in Drug Discovery at McMaster University. He completed undergraduate studies at Queen's University, followed by a PhD with Prof. Michael Kerr at the University of Western Ontario, specializing in natural products synthesis. He pursued postdoctoral studies at the Griffith Institute for Drug Discovery in Brisbane, Australia, and began his independent career at the University of Idaho before moving to McMaster University in 2017. Prof. Magolan's research program combines the development of synthetic methods with a diverse portfolio of collaborative interdisciplinary drug discovery research. |

|

Yujia Chen was born in Shenzhen, China in 2001. She received her B.Sc. in chemistry in 2019 from South China University of Technology, China. In 2024, she studied in the M.Sc. program at the University of Hong Kong, doing her thesis course under the supervision of Prof. Pauline Chiu. |

|

Yun He received his B.Sc. degree in organic chemistry from the University of Science and Technology of China in 2017. He then joined the University of Hong Kong, where he worked under the supervision of Prof. Pauline Chiu and obtained his Ph.D. in Chemistry in 2023. After graduation, he worked at a biopharmaceutical company in Hong Kong before returning to the University of Hong Kong to continue his research as a postdoctoral fellow. |

Copyright © 1921-, Organic Syntheses, Inc. All Rights Reserved